By Kat McDaniel, Principal at MEDiAHEAD

By Kat McDaniel, Principal at MEDiAHEAD

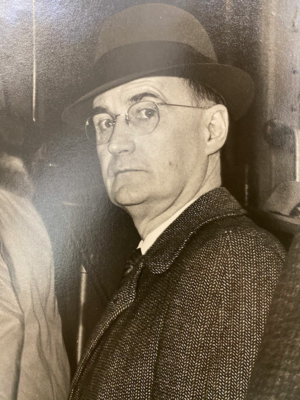

Veteran’s Day is November 11th. As we remember and support our veterans, I wanted to do more than a quick thank you. I wanted to share a personal story about my grandfather.

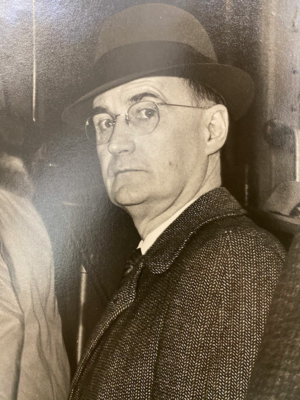

The last horse charge of American cavalry was in World War II. My grandfather, Albert E. Hallett, was in the final cavalry charge, breaking up a Japanese attack in the Philippines that bought time for the cavalrymen and other American troops.

The jungles of the Philippines are thick and fighting in them was treacherous. My grandfather was fluent in Japanese after his officer training, and he often slipped behind enemy lines for scouting and harassment. The Army didn’t have all-terrain vehicles at the time. With horses, you could cross streams, climb mountains — go anywhere. Some cavalry units even carried machine guns on horseback.

The final charge came in April 1942 as part of the months-long effort to defend the Philippines from the Japanese invasion.

The Americans on the Philippines weren’t ready for the fight, and U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur had to lean hard on his elite troops to protect the rest of the force as they withdrew to one defensive line after another. And cavalry was uniquely suited for that mission since it could ride out, disrupt an attack, and then quickly ride back to where the rest of the defenders had fortified themselves.

And so MacArthur called up the 26th Cavalry (Philippine Scouts), a unit that had American officers and Filipino enlisted men on horses. And all of them were well-equipped and good at their jobs. But, like the rest of the American forces there, they faced a daunting enemy. The Japanese invaders were nearly all veterans from fighting in Korea or Manchuria, but few of the American defenders had seen combat. And the Japanese forces were better armed.

The cavalry scouts were exhausted from days of acting as the eyes and ears of the Army, but a new amphibious operation on December 22 had put Japanese forces on the road to Manila. The defenders there crumbled in the following days and completely collapsed on January 16, 1942. If the 26th couldn’t intercept them and slow the tide, Manila would be gone within hours.

The American and Filipino men scouted ahead on horseback and managed to reach the village of Morong ahead of Japanese forces. The village sat on the Batalan River, and if the cavalrymen could prevent a crossing, they could buy precious hours. But as they were scouting the village, the Japanese vanguard suddenly appeared on the bridges. The commander had no time, no space for some well-thought-out and clever defense from cover. It was a “now-or-never” situation, and the 26th had a reputation for getting the job done.

Charge!

The men and horses surged forward, pistols blazing, at a vanguard of Japanese infantry backed up by tanks. But the American cavalry charge was so fierce that the Japanese ranks broke, and they dodged back across the river to form back up. It was so chaotic that even the tanks were forced to stop.

“Bent nearly prone across the horses’ necks, we flung ourselves at the Japanese advance, pistols firing full into their startled faces, a few returned our fire but most fled in confusion. To them we must have seemed a vision from another century, wild-eyed horses pounding headlong; cheering, whooping men firing from the saddles.”

The cavalrymen held the line, dismounting after the first charge but preventing the Japanese crossing.

After that charge, the story turned grim.

The cavalry men took heavy losses that day before falling back to the rest of the American force after reinforcements arrived. They were isolated on the Bataan Peninsula. As the American forces began to starve, they butchered the horses and ate the meat. But even that wouldn’t be enough.

On April 9, 1942, the U.S. forces on the Bataan Peninsula surrendered to the Japanese. My grandfather, who was MIA for 18 months, escaped the death march by hiding in the jungle until General MacArthur returned. At least 600 Americans and 5,000 Filipinos were killed in the death march that followed.

My grandfather never talked about the war or the atrocities that he had witnessed. He was tough and hard to love, but we found a common path through our mutual love of horses. He went on to become an Assistant Attorney General, a judge and later was one of the Appellant Court Judges in Illinois. He peacefully grew orchids, made grandfather clocks and frames for my grandmother’s paintings.

In 1971 he walked out into the back yard one night and tragically hung himself. At that time, we really didn’t understand PTSD, and after such a successful life we were all beyond shocked. I wish I had known him longer – he had an amazing story to tell.

To all of the veterans… thank you for your service. And thank you to the families that support the men and women that protect our country and our freedoms!

By Kat McDaniel, Principal at MEDiAHEAD

By Kat McDaniel, Principal at MEDiAHEAD

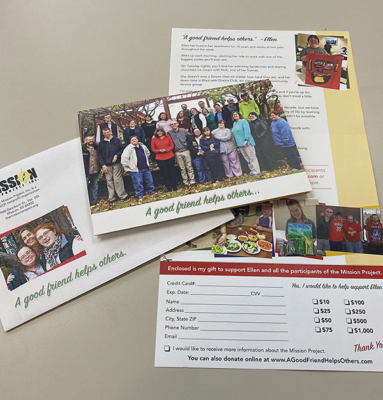

This holiday season – why not use your money to change someone’s life? Because my children are older, and my family doesn’t exchange gifts anymore, we’ve decided to make this holiday the holiday of giving to others.

This holiday season – why not use your money to change someone’s life? Because my children are older, and my family doesn’t exchange gifts anymore, we’ve decided to make this holiday the holiday of giving to others.

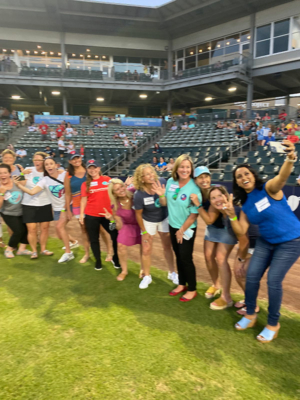

Did you know that we have an American professional women’s soccer team right here in Kansas City? It began as an expansion team in the National Women’s Soccer League in 2021.

Did you know that we have an American professional women’s soccer team right here in Kansas City? It began as an expansion team in the National Women’s Soccer League in 2021.

By

By

By

By